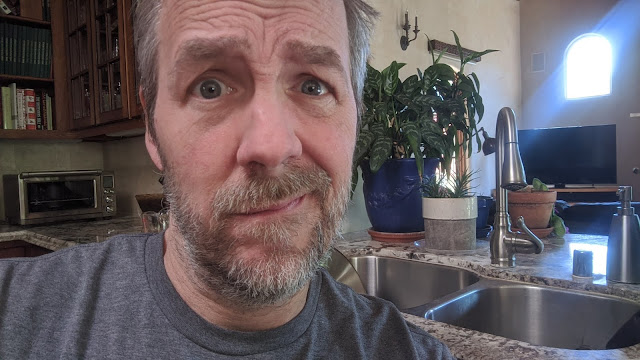

Begrudgingly Sharing My Kitchen

Oof, this one stings a bit. Before I was diagnosed with

multiple sclerosis in 2006, I was the chef of the house. I made all the

breakfasts, all the lunches, all the dinners. Laura was the baker, the dessert

maker. And we were great at our roles. Evenings were feasts and I relished

every opportunity to play in my kitchen (emphasis on MY kitchen) and experiment

with every type of cuisine this planet has to offer. And I got good at it. Real

good. Like chefy good.

As a learning cook in my twenties, though, I had my

colossal failures. So colossal, they are lore in our household, defined simply as

“incidents”—the blender incident, the cayenne pepper incident, the other

blender incident, you get the picture. How was I supposed to know that using a

knife to unjam a blender—while it was still running—was a bad, bad idea? Or

that measuring spices over a pot of soup could go very, very wrong if the lid

on your spice jar plunked off into the soup and the full jar of its fiery contents

followed suit? And that leaving a blender unattended on the edge of a

counter—spinning wildly with a red fruit smoothie mixture inside—was another

bad, bad idea? Other than using logic, there was NO way to know this.

But I learned, and my mistakes grew further and

further apart. Dinner parties were routine, and I even insisted on no potlucks.

I wanted to cook. All of it. And then MS came along.

Soon after my diagnosis, Laura started making

breakfast on a few weekends. I could, but she wanted to help, so I let her. But

for the most part I still made all the breakfasts, all the lunches, all the

dinners. I didn’t grill as much, but summertime grilling and MS don’t mix that

well, sorta like high heat and half and half (uh, don’t do that).

And then a few years ago she took over making

breakfast every weekend. I was okay with that. After all, she makes a mean

Dutch Baby pancake (with sausage or crispy bacon on the side, crisped just how I like it).

And then she was making her own breakfast some mornings. And then she was

packing her own lunches for work some days. And then she was helping me in the

kitchen some evenings. Suddenly, but not so suddenly, Laura had become my

sous-chef de cuisine.

Today? I can’t really cook without her. Her mise-en-place

assistance is invaluable, as gathering things to cook given my mobility issues includes

the risk of ushering in another ice age due to my glacial speeds. When my hands

are too tired (say, after an afternoon ride on my arm bike), she actually handles

a knife properly, a massive pet peeve of mine. And now she even cooks fish

better than I ever did. I’ll admit, I’m jealous. But proud as hell.

Sure, because of MS my duties have changed in the

kitchen, our kitchen, but I’m still a

chef. I’ll always be a chef, just like I’ll always be a snowboarder, a hiker, an

explorer. Our shared disease often requires inconvenient—and unwanted—changes,

and it is how we cope with these new realities that shapes the future richness

in our lives. We can desperately cling to what we had as the rope burns through

our hands. Or we can evolve and grow and lead fuller lives than we ever thought

possible with MS. I choose the latter.

Now it is my job to teach her about a job she never

wanted … teach her to be the chef de cuisine. Educate her on the importance of

fond when making a pan sauce. Instruct her on the nuances of how to properly bloom

garlic, the secret to cooking steak to a perfect medium rare, and why using razor-sharp

knives is essential. And nod with understanding when she has the same, ahem, incidents I had decades ago—the wooden-spoon-left-on-a-hot-pan-too-long

incident, the paper-too-close-to-the-hot-burner incident. Well, maybe not the

same incidents. She knows by now to watch out for that damn blender.

Comments

Kudos to Laura for stepping up in the kitchen.